The Hawaiian language newspapers of the 1800s printed much more than “hard news”. Their pages were also filled with moolelo: histories, legends and myths that had been passed down orally by generations of Hawaiians. These tales were printed serially, sometimes running for years. The well-known books by historian Samuel Kamakau describing ancient Hawaiian culture and legends were originally published as newspaper articles during this period.

But there were many storytellers in the papers besides Kamakau. Among them was Moses Manu, Jr., a native of East Maui. Manu (whose first name was sometimes written as Mose or Moke), wrote dozens of moolelo, and because of his familiarity with East Maui, his writings contain a treasure trove of information about Kaupo.

Four of Manu's stories in particular deepen our understanding of Kaupo's landscape:

- "Ka Moolelo o Kihapiilani" (The History of Kihapiilani)

- "He Moolelo Kaao no Keaomelemele" (A Legend of Keaomelemele)

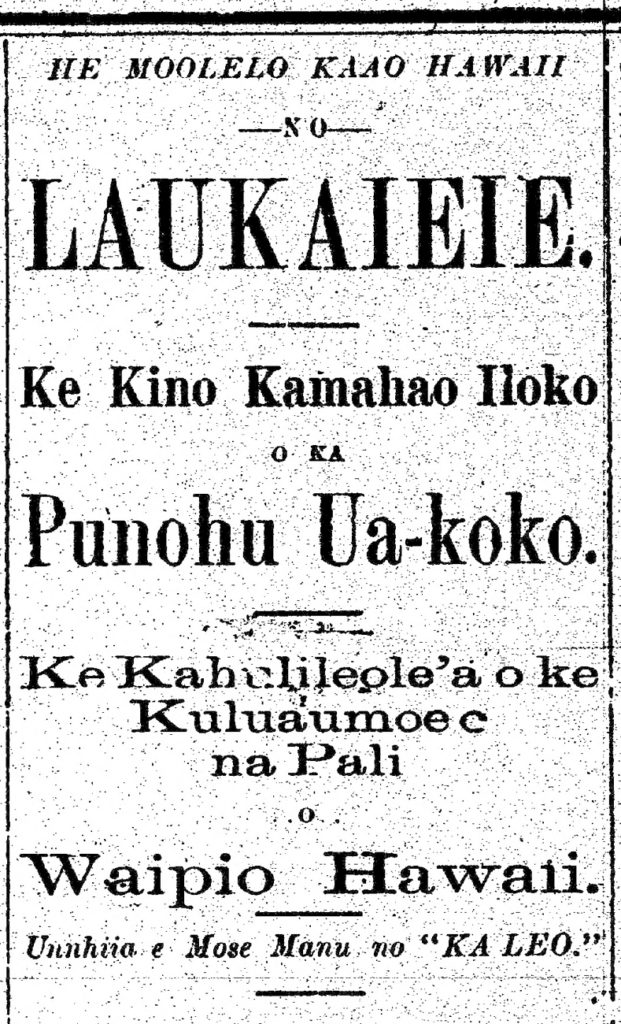

- "He Moolelo Kaao Hawaii no Laukaieie" (A Legend of Laukaieie)

- "He Moolelo Kaao no ke Kaua nui Weliweli mawaena o Pelekeahialoa a me Wakakeakaikawai" (A Legend of the Terrible War Between Pelekeahialoa and Wakakeakaikawai)

Kihapiilani (1884)

In January 1884, Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, a weekly, began printing Manu’s account of the history of the chief Kihapiilani. This moolelo presented Kihapiilani’s exploits in the 17th century to become ruler of Maui by overthrowing his brother. Kihapiilani and his wife visit priests across the island, seeking advice on how to attain their goal. There are numerous versions of the history of Kihapiilani, but Manu's is unique in situating one of these priests at Kaupo, near Loaloa Heiau:

Aole i liuliu aku ia hele ana iloko o ka wiliwili a me ka akoko, hiki laua nei i Keahuaiea, oia ka mokuna o Honuaula me Kahikinui pii aku o na puu mahoe o Luailua a me ke kahawai o Waiahualele, a hiki laua nei i ke Olepelepe, oia kahi e nana aku ai ia Kaupo i ka waiho mai, a i ke oni ae a ka lae o ka Ilio iloko o ke kai, ke hele aku nei e awakea; hoomau aku ia no laua nei i ka hele ana a pau o Kahikinui, hiki i Waiopai, ka palena o Kahikinui me Kaupo, aole he kamaaina nana e kuhikuhi mai i ke alii e hele nei, a hiki i Nuu, hele no laua nei a pii ana i Puumaneoneo, aneane lawe o lehua i ka la; aia laua e hoomaha ana ma Pohakunohaha a liuliu loa, o ka poo aku ia no ia o ka la. … Ia Kihapiilani ma e hoomaha nei a oluolu, o ka hele mai la no ia a hiki i ka pii'na o Kukoae ma Pukaauhuhu, o ka nalowale no ia o ka ili o ke kanaka, aia ma keia wahi i puiwa ae ai ka wahine a ke alii i ka maalo ana iho o keia Ilio nui keokeo mamua o laua.

(They [Kihapiilani and his wife] did not spend long traveling through the wiliwili and akoko trees, when they arrived at Keahuaiea, the boundary between Honuaula and Kahikinui, where the twin hills of Luailua rise up, and where Waiahualele Gulch is situated. They went on to Olepelepe, where they could see Kaupo, with Kalaeokailio Point jutting into the sea. They continued traveling through midday, passing through Kahikinui and arriving at Waiopai, the border of Kahikinui and Kaupo. There were no residents to guide the chief on his way as they went on to Nuu. As they climbed up Puu Maneoneo, the sun had almost set [literally, "Lehua Island had nearly taken the sun"]. They rested at Pohaku Nahaha for a long time as the sun went down. After Kihapiilani and his wife had rested, they went on to climb Kukoae at Pukaauhuhu while it was too dark to even see one's skin. At this place, the chief’s wife was surprised when a large white dog passed before them.”)

As the story continues, Kihapiilani recognizes this dog as the spirit Kihawahine. The dog leads Kihapiilani to the priest’s house and then vanishes. After spending a few days in Kaupo, the priest sends Kihapiilani and his wife to Kipahulu with a guide:

Ia lakou nei i hele mai ai, iho koke mai la no lakou nei i ke kahawai o Manawainui, a pii aku la ma kela aoao, huli ae nana o ke kula o Niniao, a me ka waiho mai a kai o Makulau, kahi a Keaka i noho ai, a launa'i me Pamano; hele aku no lakou nei a hiki i ka heiau o Pohoiwi, ka lua o na heiau nui ma Kaupo, huli iho nana o ka huai a ka wai o Punahoa, a iho aku o maalo kahi e waiho la kapuahi a Eleio, kekahi o na kanaka mama oia au i hala aku la. Ia lakou nei e hele ana iluna aku o Ai-he a iho aku i ka pali o Nuanualoa, ke hahai nei ke kamaaina i na inoa o na aina o Kaupo, pela wale no lakou nei o ka hele ana a hiki wale i Naoupuu, a iho aku i ka pali o Kalepa. Ia lakou i hiki aku ai ilalo, olelo aku la ke kamaaina i ke alii, auhea olua e na malihini, heaha? wai a ke alii, eia ke alanui malalo nei o Kahaka, a eia no hoi ke alanui e pii ai maluna o Nahunonapuu, o ka palena keia o Kaupo a me Kipahulu.

(As they went on, they quickly descended to Manawainui Stream. They climbed the far side and turned to look up at the fields of Niniau and seaward to Mokulau, where Keaka lived and played with Pamano. They went on to Popoiwi, the second of the great heiau of Kaupo, and turned to look down at the surging water of Punahoa. They went down to Maalo with its fireplace of Eleio, one of the swiftest people of ages past. As they ascended Kalaeoaihe and went down the cliff at Nuanualoa, the native told the names of the lands of Kaupo. They went on until Naopuu, descending the cliff at Kalepa. As they reached the bottom, the native said to the chief, "Take note." When the chief asked why, the native responded, "Down here is the road of Kahaka, and from here the road goes up to Nahunonapuu. This is the border of Kaupo and Kipahulu.")

There are a number of characteristics in Manu's history of Kihapiilani that recur in his later stories.

First, Manu takes care to note the boundaries of Kaupo district. Waiopai in the west demarcates the border with neighboring Kahikinui district. In the east, Kalepa Gulch, and specifically an area at the bottom called Kahaka, marks the dividing line between Kaupo and Kipahulu.

Next, Manu cleverly inserts references that would only been recognizable to those well-acquainted with Kaupo's geography and history. For instance, after leaving the area of Pohaku Nahaha, Kihapiilani encounters a white dog at Pukaauhuhu that leads him to the Kaupo priest. Readers familiar with the region would have been aware that immediately shoreward of Pukaauhuhu is Kalaeokailio, which roughly translates to the "promontory of the dog". Tellingly, Manu also notes that Kalaeokailio is the first Kaupo landmark Kihapiilani spies while traveling through Kahikinui on his way to Kaupo.

Finally, Manu records why certain areas in Kaupo are notable by referencing that famous people and deities of that place. Thus, the shore area of Mokulau evokes the legend of the surfer Pamano and his adopted sister Keaka. Nearby, Maalo Gulch is connected to the fabled runner Eleio.

Keaomelemele (1884-1885)

In August 1884, “Ka Moolelo o Kihapiilani” ended its run in Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. The next month, the same newspaper began publishing Manu’s account of the legend of Keaomelemele. In contrast to the Kihapiilani history, rooted in relatively recent events (in Manu’s time), "Keaomelemele" and Manu’s later moolelo are set in a mythical past inhabited by gods and spirits. At one point in "Keaomelemele", Manu discusses the origin of moo (lizard spirits) and their famous abodes across the Hawaiian Islands, including Kaupo:

O Kamakilo, oia ka moo ma Kahikinui ma Maui nei, aia kona kiowai ma Waiopai e waiho nei, oia ka mokuna o ka aina nana i hookaawale ia Kahikinui a me Kaupo; he kahawai nui keia, a he wai omaomao mau hoi kona i na manawa a pau a aohe hoi ona kau e pio ai. Ua oleloia hoi ma kona moolelo, he moo keia i hanauia mailoko mai o ka wahine kanaka maoli, he mau mahoe laua, aia ma keia ano, ua lawe ae na makua a hoomana aku ia laua ma ke ano i akua, a ua oleloia hoi laua he unihipili, pela i lehulehu ai na moo i ka wa kahiko; a no ka hele o keia mau moo i kauhale ma ke ano kino eepa i like me ko ke kanaka mau hiohiona hoopohaohao e noi ai i ka laua mea e makemake ai, nolaila i kapaia ai o Kamakilo. He mau moo keia i komo ole iloko o ka papa hoonohonoho o na moo mai kinohi mai, aka, ua manao wale aku no paha na kanaka o ia au e hoomana aku ma ka inoa o ka moo alii nui o Maui nei, oia hoi o Kihawahine.

(Kamakilo is the lizard spirit at Kahikinui here on Maui. Its pool is at Waiopai, the area separating Kahikinui from Kaupo. This is a large stream, and the water is always green. It has never had a period where it was dry. It’s said in legend that this spirit was born as twins from a human woman. Because of their form, their parents worshipped them. It is said that these twins were the spirit of one who had passed away, as were many moo in ancient times. These twins were called Kamakilo [the beggars] because they went to houses appearing as humans asking for the things they wanted. These twins are not among the list of the earliest moo, but the people of this era deign to worship them in the name of Kihawahine, the supreme moo of Maui.)

Like in "Kihapiilani", Manu specifies that Waiopai is the western boundary of Kaupo. But here he adds another layer of why the place is important by identifying the pond at Waiopai as the home of lizard spirits. Also of note, although the gulch at Waiopai is nearly always dry in current times, it appears from Manu's writings that in the 1880s the pond there was always filled with water.

Laukaieie (1894-1895)

After "Keaomelemele", nearly 10 years elapses before Manu published another legend referencing Kaupo. In January 1894, Manu’s version of the legend of Laukaieie began in two separate newspapers, the daily Ka Leo o ka Lahui and the weekly Nupepa Ka Oiaio. In one section of this legend, the deity Makanikeoe travels through the Hawaiian Islands seeking underground water sources:

Ua hiki aku oia ma ke kiowai o Waiopai ka home o kela wahine kaulana he moo, o Makilo ka inoa. o ka palena keia o Kahikinui a me Kaupo, aia no hoi ma keia wahi i huli hou aku ai kana huakai hele no ka moana.

A iaia e hele nei me ka mama loa aole he mau lua e ae ma keia wahi ana e hele nei, nolaila ua huli hou oia iuka o ka aina, a mawaena o Nuu a me Waiu, he wahi a a keia a ka Pele e waiho ia, ua komo aku oia ma kekahi lua a hoea mauka o na kula ma Kuaihulumoa, he lua wai keia e kahe ana o hoea ikai o Waiu, i ka po a me ke ao a hiki i keia wa.

Aole he kau e pio ai o kela wai, a ua hele hou aku ka lua o ka mana a hoea ma Waipu ma ke kuono o Kalaeokailio, a ua huli hou aku o Makanikeoe i ke kumu o ka wai i kahe mai ai, a ua hiki aku oia ma ka hapalua like o ka pali o Helani.

A oiai oia e nana iho ana i ka puu o Kauhao, kahi hoi i pepehiia ai o Pamano e na kanaka o ke alii Kaiuli, kela moolelo aloha nui wale oia mau la koliuliu i hala aku la, a ka muli ponoi o kona makuahine i imi ai i mea e make ai ka laua keiki a i puka mau ai hoi kana olelo i na manawa a pau. “I make o Pamano i ka i’o ponoi.”

Aia Makanikeoe ma keia pali kiekie launa ole mai, ua alu koke iho la oia a hiki pono malalo o ke kumu o ka pali a loaa aku la iaia ke kumu o ka wai malalo pono o ka puu o Ahulili a ua kahe mai kekahi mana wai uuku ahu ma Waikaia, o keia wai ka mea nona keia mau lalani mele hou a Pamano.

“E ka pilipiliula i ka la—e,

I ula i ka la o Waikaia,

Kaina’ku la oe i ke ahupuaa,

Ua hue paha oe—a.”

A he nui a lehulehu wale na mana wai liilii ma keia aina o Kaupo, a mai loko mai o ke kumu o keia wai, ka wai e hu ala ma ka Paala ma ke kahakai o Punahoa, a ua huli hou aku la ke kamaeu no loko o ke kai a hiki ma ka lae o Kumukapele ma Hopilo.

A ua komo hou aku oia ma ia lua a hoea mauka loa o ke kuahiwi, o Alewa ka inoa o keia lua, ua kanuia e ka poe hele kuahiwi i ka ke Neleau a puni, i ole e haule a poino ka poe kalai waa i ka wa kahiko, a ke ulu nei ke Neleau a hiki i keia manawa, a ma ia hope iho, ua hala hou oia ma ka moana.

A ua loaa hou iaia kekahi lua hohonu makai aku o ke kekahi koa i’a kaulana ma Kaupo, aole he maikai o lalo o keia lua, he nui na pohaku olapalapa maloho, a he nui wale nae o na ano i’a a pau e noho ana maloko o keia lua, a mai loko mai o keia lua e pu mai ai ka i’a a noho ma kahi papau o ke ko’a oia hoi o Napuoa ka inoa o keia ko’a i’a ma Kaupo, ano keia ko’a keia mau lalani mele.

“Aia paha ko mai,

I kai i Napuoa,

He ko’a i’a ole ia,

He uu maka maunu,

Hei wale ae ka makau,

O ka mali kona lua.”

Nolaila, e waiho kaua e ka mea heluhelu i ke kamailio ana i na makamaka o ka aina nona Kaupilipapohaku o Kaupo, a me ka wai luu poo o Manawainui, na lakou e ike a hoomaopopo i keia mau hoakaka.

A he mea pono e hele aku kakou imua ma ka aina o ka mea e kakau nei i keia moolelo kaao, o Hawaii nei, ka mea hoi nona ka makani kaulana he kaili aloha o Kipahulu. …

Ia Makanikeoe i haalele aku la ia Kaupo ma kona hele ana a’e maluna o ka ili o ke kai, e like me Makuakaumana ke kaula nana i hele wawae ka ili lau mania o ke kai ma ka moana nui akea, a hiki i na kukulu o tahiti.

A pela pu no hoi ko kakou Haku Iesu Xaristo i hele ai maluna o ka moanawai Garilaia oia ka mea nana i olelo a papa aku i ka makani e noho malie, a oia ka mea nana i hoopahaohao i kana poo haumana, a pela no hoi ka eueu o Hawaii e hele nei maluna o ka ili o ke kai.

I ka hala hope ana ae o Kaupo ua huli ae la kona mau nanaina i na pali nihoniho o ua aina huli ala i ke alo makani, ua kaalo ae la oia mawaho o ka pali keikikane o Kaupo a me Kipahulu, oia o Kalepa, a o ka mokuna hoi keia o Kahaka ka inoa.

(He arrived at the pool at Waiopai, home of that famous female lizard spirit called Makilo. This was the border between Kahikinui and Kaupo. Here, Makanikeoe again followed the oceanside.

He went quickly, as there were no other pits in this area. So he turned inland between Nuu and Waiu, an area filled with volcanic rocks left by Pele. He entered a tunnel and emerged upland of the plains at Kuaihulumoa, an underground stream that has flowed continually down to the sea at Waiu to this day.

There is no period when the water has stopped flowing, and a secondary branch flows on to Waipu at the base of Kalaeokailio Point. Makanikeoe continued his search for the source of the water and arrived halfway up the cliff of Helani.

Here he looked at the hill of Kauhao, the place where Pamano was killed by the subjects of the chief Kaiuli in that beloved story from the dim days of long ago, and where his uncle [mother’s younger brother] sought the substance to destroy their child, from which comes the enduring expression, “Pamano died by his own flesh and blood.”

Makanikeoe was on this towering cliff and quickly descended until he was at the bottom. There he found the source of the water directly beneath the hill of Ahulili. A small stream flowed from Waikaia, the water noted in these lines of a chant from Pamano.

“Downy pilipiliula grass in the sun,

Red in the sun of Waikaia,

Leading you to the ahupuaa,

You are exposed.”

There were many small streams in this area of Kaupo, and this is the source of the water that gushes forth at the worn-smooth rocks at the shore of Punahoa. Then the protagonist searched the sea all the way to Kumukapele Point at Hopilo.

He again entered the tunnel and arrived up in the mountains. The name of this tunnel was Alewa. It was covered in the neleau shrub planted by mountain travelers so that the canoe carvers of old would not fall and be hurt. The neleau continues to grow to this day. After this, he went out into the ocean again.

He found a deep hole in the sea out from a famous fishing shrine in Kaupo. The bottom of this hole was not smooth. There were many jagged rocks. Many types of fish inhabited this pit. The fish would be gathered in to reside in the shallows of the shrine. The name of this fishing shrine in Kaupo was Napuoa and is the subject of these lines of song:

“Perhaps yours,

Is in the sea at Napuoa,

A shrine without fish,

A raw soldierfish is the bait,

The fishhook catches,

The fishing line is her companion.”

Here, reader, let us leave the conversation to the friends of the land of Kaupo and Manawainui, where the rain clings to the rocks and the water leaps from the precipice, as they know and remember these explanations.

We must now go on ahead to the land of the one who has written this legend of Hawaii, the one of the land of the famous love-snatching wind, Kipahulu. …

Makanikeoe departed Kaupo traveling over the surface of the sea just as did Makuakaumana, the prophet who walked on the surface of the open sea all the way to the “Pillars of Kahiki”.

Just as our Lord Jesus Christ walked on the Sea of Galilee and commanded the wind to be still, to the amazement of his disciples, so did this hero of Hawaii walk across the surface of the sea.

As he passed from Kaupo, he turned to view the jagged cliffs of that land turned to face the wind. He passed through the foothills of Kaupo and Kipahulu at Kalepa, at the borderland called Kahaka.)

In "Laukaieie", Manu again notes Waiopai as the western boundary of Kaupo and Kalepa in general and Kahaka specifically as the eastern border. He also repeats the reference to Waiopai’s lizard spirit from "Keaomelemele". But in typical Manu fashion, he builds on what he has said previously, in this case, to reveal that the lizard spirits are female.

Particularly intriguing is the description of the underground water sources. According to Manu, the same underground stream in Nuu that feeds Waiu Spring near Puu Maneoneo is connected to Waipu Spring at Kalaeokailio Point, water sources near Kauhao Ridge and Ahulili Hill in Manawainui Valley, and Punahoa Spring along the Mokulau shoreline.

Manu again references the legendary figure Pamano, and here he adds a clue for those familiar with that legend and Kaupo geography. As Manu writes, Makanikeoe leaves Waipu Spring at Kalaeokailio Point and climbs Kauhao Ridge, where his uncle sought the “substance” (awa plant) used to intoxicate Pamano before he is dismembered. Astute readers would have caught on that the name of Pamano’s uncle was Waipu, the same name as the spring that Makanikeoe had just left.

Pelekeahialoa (1899)

From May to December 1899, the weekly Ka Loea Kalaiaina published a legend from Manu about the famous lava deity Pele, in “He Moolelo Kaao no ke Kaua nui Weliweli mawaena o Pelekeahialoa a me Wakakeakaikawai”. One installment of this legend mentions Kaupo. Unfortunately, the relevant newspaper issue not available in online newspaper databases, but Hawaiian scholar Mary Kawena Pukui had access to this issue in the Bishop Museum archives and produced a translation published in the book "Sites of Maui":

"After Pele accomplished her wondrous deeds on Maui, she left her relatives at Kealaae and Nanualele. She returned to Hale-a-ka-la and began to dig a deep pit and made sixteen cinder cones that stand to this day. She went visiting below Paukela, Naholoku and Maua. There were broken bubbles (kipukapuka) in the lava beds from above Maua to Kumunui and all the way to Paukela. Paukela was a chiefess of Kaupo in the legend of the high chiefs of Maui. Lava beds are seen at Kakio, Puuomaiai, and Puu Maneoneo all the way down to the sea of Kou. Found there is the most peculiar flow of water Pele made. The name of it is Waiu and it flows to this very day in which we are telling this tale. This water comes out of a hill of red rocks and cinder similar to Kauiki hill. At Nuu, on the windward side, the lava had covered it from Pohakuulaula down. Kalou was the place where the line of the ship, Claudine, was attached and where the wharf of Nuʻu is now located. The late Queen Kapiʻolani owned that land. The lava went on and ended at Huakini in Kaupo."

"Pelekeahialoa" was Manu’s final story that contained references to Kaupo. While the passage above is short, it contains tantalizing bits of information. Manu describes Pele’s journey from Naholoku and Maua village, near Kaupo Gap, down through Kumunui ahupuaa to the shoreline at Paukela, then westward to Puuomaiai, near the present-day St. Joseph Church, and finally on to Puu Maneoneo, overlooking Nuu Bay. Manu provides the rarely heard place name of Kalou, being the area around Nuu Landing, and also records that Paukela was the name of a former chiefess as well as being a place name.

About Moses Manu

Those interested in Manu's writings are naturally curious about his life. The records are sparse, but we do know a few key details about his life.

Manu was probably born in the mid-1850s, based on the information that Manu's father, Manu Kahunaaiole, was born in 1837, and Manu Kahunaaiole's wife, Pili, the likely mother of Moses Manu, died in 1858. In "Keaomelemele", Manu references "kuu mama, Mrs. Kahele." However, this refers to his mother-in-law Anahua Kahele, the second wife of Manu Kahunaaiole.

Moses Manu and his wife, Mere, celebrated the birth of a son in 1882. Through the 1880s and 1890s, Manu wrote a number of moolelo for Hawaiian-language newspapers—many more than the four mentioned above. He also provided stories to foreign-born historians Abraham Fornander and Thomas Thrum that they included in their books and almanacs.

Manu spent most of his life in his homeland of East Maui. He was living in Kipahulu in 1882 when his son was born. In November 1888, he penned an article for Ko Hawaii Pae Aina and noted his residence as Kipahulu. In April 1893, he was appointed to run the government pound in Kipahulu, where he was responsible for rounding up and returning (or selling) stray livestock.

During this period, Manu was also politically active in the resistance against the United States’ overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and the subsequent annexation in 1898.

In November 1896, Manu served as the Kipahulu delegate for the meeting of the Hui Aloha Aina, a political party that opposed the United States’ actions. In October 1900, in the last known direct reference to Manu, he was noted as a delegate at a convention of the Independent Party, successor to Hui Aloha Aina.

Finally, an article in Ka Naʻi Aupuni in March 1906 described Moses Manu in a way that indicated he was still living at that time, calling him "kekahi kanaka Hawaii hoopuka moolelo Hawaii kahiko" (a Hawaiian who produces histories of ancient Hawaii).

Note: Kui Gapero and Puakea Nogelmeier assisted with biographical details of Moses Manu.

1 thought on “Moses Manu, East Maui storyteller”